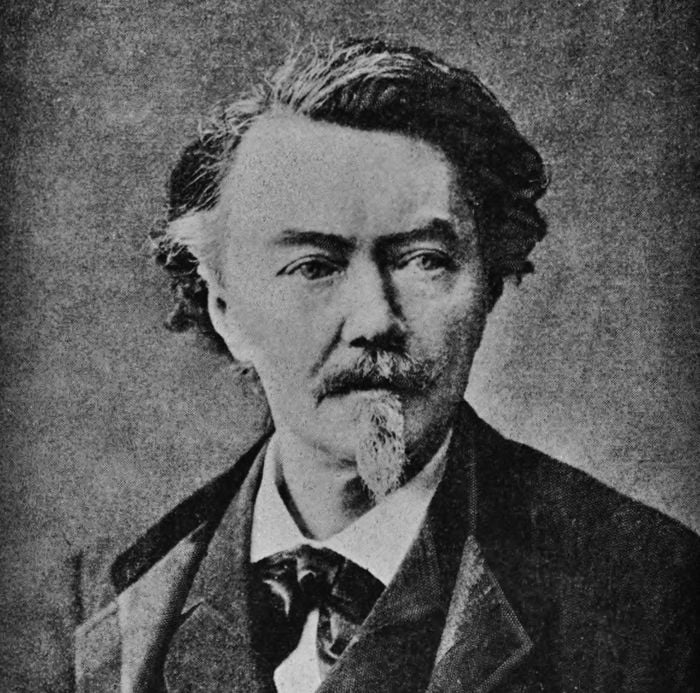

Villiers de L`isle Adam (1838-1889)

Count Villiers de l`Isle Adam, bom in Brittany in 1838, led a strange life. “Born without average will-power,” says Huneker, “except the will to imagine beautiful and strange things, all his years he fought the contending impulses of his dual nature.”

He was the very model of a bohemian. His strange tales, the best of which are collected under the title Cruel Tales, are fantastic prose poems in the manner of Poe. The Torture of Hope, according to Huneker, recalls Poe at his best.

The present version, anonymously translated, is reprinted from an American collection of tales, not dated. It is from the volume of Cruel Tales.

The Torture of Hope

Many years ago, as evening was closing in, the venerable Pedro Arbuez d`Espila, sixth prior of the Dominicans of Segovia, and third Grand Inquisitor of Spain, followed by a fra redemptor, and pre¬ceded by two familiars of the Holy Office, the latter carrying lanterns, made their way to a subterranean dungeon.

The bolt of a massive door creaked, and they entered a mephitic in pace, where the dim light re¬vealed between rings fastened to the wall a bloodstained rack, a brazier and a jug. On a pile of straw, loaded with fetters and his neck encircled by an iron carcan, sat a haggard man, of uncertain age, clothed in rags.

This prisoner was no other than Rabbi Aser Abarbanel, a Jew of Aragon, who—accused of usury and pitiless scorn for the poor—had been daily subjected to torture for more than a year. Yet “his blind¬ness was as dense as his hide,” and he had refused to abjure his faith.

Proud of a filiation dating back thousands of years, proud of his an¬cestors—for all Jews worthy of the name are vain of their blood—he descended Talmudically fromOthoniel and consequently fromlpsiboa, the wife of the last judge of Israel, a circumstance which had sustained his courage amid incessant torture. With tears in his eyes at the thought of this resolute soul rejecting salvation, the venerable Pedro Arbuez d`Espila, approaching the shuddering rabbi, addressed him as follows:

“My son, rejoice: your trials here below are about to end. If in the presence of such obstinacy I was forced to permit, with deep regret, the use of great severity, my task of fraternal correction has its limits. You are the fig tree which, having failed so many times to bear fruit, at last withered, but God alone can judge your soul.

Read More about The Prodigal Son 1