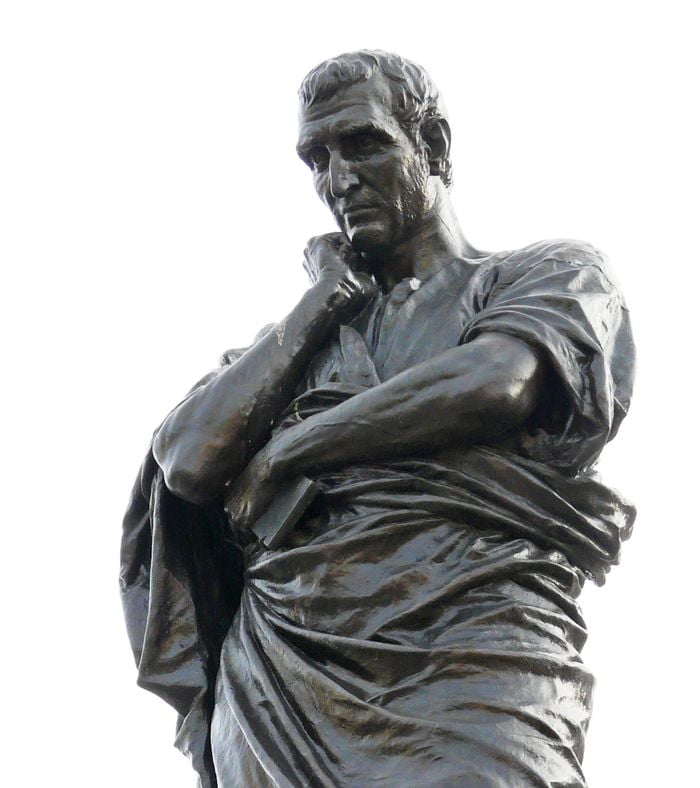

Orpheus and Eurydice – Ovid (43 B.C.—18 A.D.?)

Publius Ovidius Naso, better known to readers of English as Ovid, was born not far from Rome, and spent the latter part of his life in exile. The Metamorphoses, his most ambitious work, is an attempt to reshape in metrical form the chief stories of Greek mythology; and several from Roman mythology. Orpheus and Eurydice, one of the most human of the legends of antiquity, is a graceful piece of writing. Its “point” is as clear and as cleverly turned as you will find in any ancient tale.

The present translation is based by the editors upon two early versions, the one very literal, the other a paraphrase. The story, which has no title in the original, appears in the Tenth Book of the Metamorphoses.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Thence Hymenaeus, clad in a saffron-colored robe, passed through the unmeasured spaces of the air and directed his course to the region of the Ciconians, and in vain was invoked by the voice of Orpheus. He presented himself, but brought with him neither auspicious words, nor a joyful appearance, nor happy omen.

The torch he held hissed with a smoke that brought tears to the eyes, though it was without a flame. The issue was more disastrous than the omen; for the new bride, while strolling over the grass attended by a train of Naiads, was killed by the sting of a serpent on her ankle.

After the Rhodopeian bard had bewailed her in the upper realms, he dared, that he might try the shades below as well, to descend to the Styx by the Taenarian Gate, and amid the phantom inhabitants, he went to Persephone and him who held sway over the dark world. Touching the strings of his harp and speaking, he thus addressed them.